Finding your style

My personal journey in the pursuit to develop a personal style.

0. Prologue

I will come back to write about my life experiences from time to time, and the post that you are going to read is one of them, compressed into a few paragraphs and a Call To Action to all my fellow creatives out there.

“Not all those who wander are lost.” wrote J.R.R. Tolkien, referring to Aragorn's journey to become king of Gondor. The phrase has always stuck with me, since I was a 12 years old boy reading Lord of The Rings for the first time. Maybe, I was already forging my path, unconscious but filled with hope and ideas.

I got lost and found myself again a lot of times. I got lost when fear of failure, comparison with others, other people's opinions, and a load of generic negativity took hold of me. I found myself again when I learned to let go. Let go of expectations and the fear of failure, let go of comparison and negativity. Let go of my ego.

I learned to be who I am shaping my persona and my path through experience, trial and error, and surrounding myself with the right books and people at the right time.

It is a never-ending process of discovery and adventure within oneself, one that is worth doing, taking all the experiences for what they are, a mean to find and shape myself, without useless labels.

“The only journey is the one within.” - Rainer Maria Rilke

1. The Beginning

For years, I have been photographing mountains and everything tied to them. Whether for leisure or work, my life revolved mostly around this environment.

I practiced rock climbing, trail running, and hiking, and all my plans were about doing things on this huge pile of rocks. Even my reading was all about alpinism, mountaineering, and the like. I was enamored with that environment, that’s for sure.

Since childhood, growing up in the grey, shabby suburbs of Naples, Italy, I would often gaze at the distant mountain ranges—the Apennines, the Amalfi Coast Mountains (Lattari), and, of course, Vesuvius, both menacing and beautiful. I still remember a family trip to the Dolomites in 2006; I was in awe, admiring those towering cathedrals of rock in all their majesty. Little did I know that a decade later, I would find myself returning there at least once a year, capturing climbers and runners through my lens.

My parents were never adventurous or outdoorsy. To them, such places were nothing but dangerous and, in some way, pointless. They let me make my own choices but never truly trusted what I was doing, offering, from time to time, unwanted advice or hurtful judgment. But could I blame them? The only reality they had ever known was that of the same grey, shabby suburbs where they had grown up.

At 21, I was a frustrated young man, prone to bursts of rage over nothing. The only thing I knew for certain was that I wanted to be a photojournalist. But I had to face the harsh reality of Naples and Italy: if you’re a young photographer without wealthy parents, strong connections, or a mentor, you’ll likely be exploited. And for a while, that’s exactly what happened—until I’d had enough. That’s when I decided to plan a solo bike trip from Naples to Trento: an 800-kilometer ride from south to north.

2. Evolution

The trip had changed something in me. It made me deal with loneliness, responsibility, risk and confidence. Damn, it built the foundation of my confidence, that until then was close to zero. In few words, it made me understand that, getting out of my comfort zone, a different reality was possible.

That’s when I started to look at mountains not anymore like something unreachable, but as a possibility.

Fast forward to some years later, I gained experience outdoors in a variety of environments, hiking, climbing rock and ice, feeling happy whenever I was outdoors: the mountains were becoming my sanctuary, my psychologist, my home.

I was spending a lot of time outdoors, alone and with others. I was not scared anymore of doing stuff alone. On the contrary, it’s a dimension I craved more and more.

I started shooting friends and climbing, then started with athletes. In one year time, I took photos for a climbing guide, sold some pictures to a climbing brand, and got the first big campaign shoot for a technical hiking shoes brand. Year after year I kept going on, working and collaborating even with huge brands such as The North Face and La Sportiva, hanging from the vertical walls of Dolomites.

I was thrilled, especially because, coming from Southern Italy—a region often overlooked by the Outdoor Industry—I was carving my path into it.

Then, COVID-19 happened. It was a huge setback for the industry and for me.

I got a smart-working job as a UX designer. It wasn’t made for me, but gave me money to survive. I went into it with the idea of abandoning a career path in photography.

That year only, without putting my name out there even once, I got called to shoot two brand campaigns, a BMW editorial and my first call with The New York Times, again traveling to the Dolomites. I took it as some sort of cruel sign from destiny, which I don’t believe. After a while, I decided to give my resignation from the job and got back into photography, unaware of the next storm that was going to hit me.

3. Change

For the past five or six years, my life and photography had revolved entirely around the mountains—their sports, their lifestyle. Even my personal projects were just an excuse for another expedition, another peak to climb, hike, or run.

In 2023, a month after resigning from my UX designer job, I set out on a thru-hike: the Translagorai trail. An 80-kilometer route in northern Italy, it’s one of the wildest due to its lack of structures or roads. I did it unsupported in three and a half days, walking about ten hours a day, covering 20 kilometers daily. It left me with… nothing.

A month later, I was in the Western Alps, shooting for an Alpine Guide Association, climbing Monte Rosa—a 4,554-meter peak in Valle d’Aosta. It was nice to stand on top, to feel my body move at that altitude with ease. But that was it. Just nice, I guess.

I was still climbing, still hiking, still doing everything I had been doing for years. But the emotions, the peace of mind—those were missing. By early 2024, the first two months were rough. I lacked the motivation to go out. I didn’t feel excited to be outdoors.

That’s when I realized: the mountains had lost their magic. They had once been a place of healing, a space where I had poured all of myself. Now, they were just what they had always been—mountains. A place to spend time, to enjoy, but nothing more. No deeper meaning, no purpose, no grand endeavors to justify activities that simply ended in themselves.

4. Out of the comfort zone, again

This past year has been one of the most prolific in terms of ideas and projects.

As soon as I let go of the mountains—where I still go and still work—my mind ignited with new ideas, disconnected from the world that had consumed me for years.

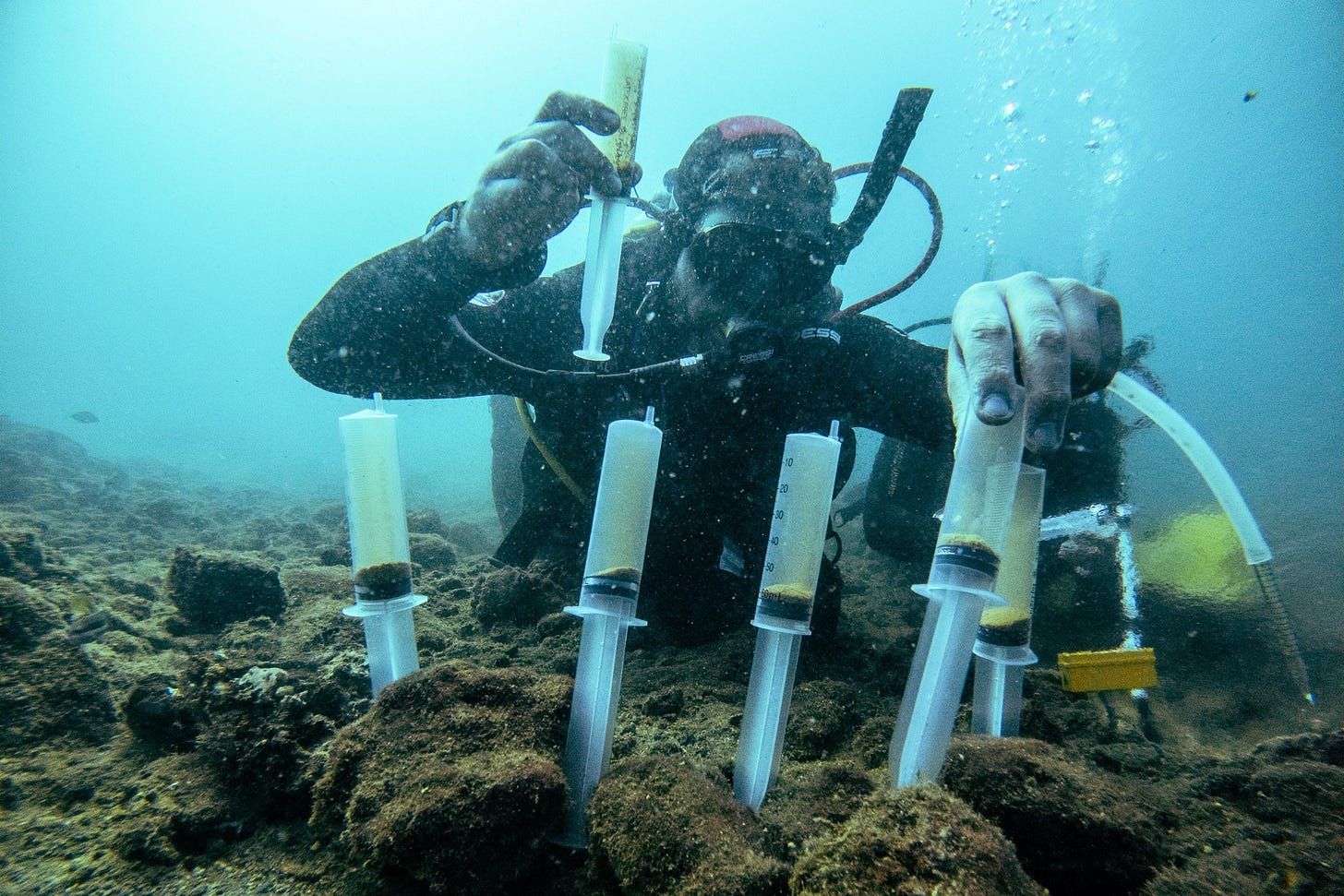

I began collaborating with scientists, met a hermit, traveled to a small village in Southern Calabria to speak with and photograph people preserving a dying language, and shot underwater images with PhD students. I made new meaningful connections and broadened my perspective in ways I hadn’t expected. I even started a project in Naples—something I had never considered before.

What once saved me had begun to hold me captive. All it took was another leap of faith into the unknown—one that continues to this day, but is now filled with discoveries and new opportunities. I pushed myself to reach out to people, to overcome the fear of rejection, and to establish deeper, more empathetic connections with the subjects I photograph.

I also returned to studying photography, this time through the works of masters like Sebastião Salgado, Alec Soth, Jonas Bendiksen, Tim Herrington, Ragnar Axelsson, Todd Hido, and others. Their work didn’t just make me a better photographer—it made me a better observer, a sharper critic, and a ruthless editor of my own images.

5. Finding your style

Expanding my perspective gave me the tools to develop a stronger visual language, allowing me to explore creative possibilities I had never considered. What pushed me in this direction was discomfort—the same discomfort that once drove me to exceed my limits had, over time, become my comfort zone.

Being in a comfort zone feels good at times, and I believe everyone should have one. But—here’s the twist—you should never stagnate in it. Creatives, and anyone with a passion, need change from time to time to keep their minds fluid and open. Just as wind prevents air from becoming stale and flowing water keeps it from festering, new stimuli keep our thoughts moving, invigorate our minds, and spark curiosity toward new things.

Only in this way can you become a prolific creator: Learn, create, fail, try again, fail better, learn, refine, challenge your vision—repeat.

6. Get into action

Whether you are a photographer, a painter, a musician, or a writer, I’d like to leave you with some actionable insights:

Ask yourself where you are in life and where you’d like to be. Don’t be afraid to answer this question, even if it stirs up insecurities. Most of us are not where we’d like to be, but only by acknowledging and accepting that can we begin to be brutally honest with ourselves—and set ourselves on the right path.

Get informed and study: Studying what others have created before us, as well as what other creatives are doing right now, can spark new ideas, challenge our current style, and help us differentiate ourselves from others.

“It is better to fail in originality than to succeed in imitation.” — Hermann Melville

Write down your ideas. Don’t let your ideas stagnate in your mind, as they’ll eventually be lost—trust me, I have some experience with this. Writing your thoughts and ideas down is a powerful way to solidify a concept or project in your memory. My advice is to use a paper notebook: the act of writing by hand helps you remember the idea. Avoid phone notes—they’ll get buried in a pile of digital clutter.

Make time to work on your ideas. Studying and writing may feel fulfilling, and you might feel like you're already achieving a lot. But in reality, you’re not—until you get out there and start making something.

Embrace failure. This is a big one. Fear of failure can be a major setback for our projects. Whenever we overthink or feel like we can’t do something the way we imagined, we might feel disappointed and frustrated. We may feel like we’ve failed. The good news is, this is exactly how the creative process works. No one—not even Leonardo da Vinci—created something perfect from the start.

Have fun. Don’t forget to have fun, in any way possible. Remember that your creative space is your inner sanctum, where you express yourself. Even in your darkest moments, let a single ray of light shine for a while.

Take some time off. Creating is surely fun, and thinking of new ideas and projects is exciting. It can be mentally draining, though. If you feel like you’re giving your 100% to something without a moment of rest, try to pay attention to it and gently force yourself to take some time off. It will renew your energy and possibly spark fresh ideas.

That’s it for now! What are your takeaways? Do you have a story you’d like to share? Do you have any advice you’d like to add to the list? Let me know, join the chat and comment on this post!

Updates: From 20th to 23rd of February I’ll be in Paris. Feel free to shoot me an email at f.guerraphoto@gmail.com.

Projects: I’m organizing a personal project in Naples focused on a side of the city that few magazines have covered—one that’s far removed from the commercial and ever-present tourist perspective.

Reads: Currently reading two books: Cathedral by Raymond Carver, and Prophecies, Fables and Bestiary by Leonardo da Vinci.

Music: In dreams - Ben Howard

Let’s connect!

Website: www.francescoguerraphoto.com

Instagram: @francescoguerraphoto

Really great read. Very insightful. Thanks for sharing your experiences.